Rudy Giuliani and his advisers walked into a nondescript meeting room in the state Senate Dec. 1 to discuss a gambit that could alter the results of the 2020 election. In that meeting were the two people President Donald Trump's team viewed as central to flipping Arizona.

The goal was simple: Arizona House Speaker Rusty Bowers and Senate President Karen Fann could help replace the state’s 11 presidential electors, whose votes were supposed to go to Democrat Joe Biden, with electors for Trump.

Biden won Arizona by the narrowest margin in the country, just 10,457 votes, and the state’s GOP-controlled state government presented what appeared to be an inviting opportunity.

Trump and his allies, including Giuliani, had for weeks pointed to purported irregularities in Arizona, claiming they contributed to a stolen election. A day earlier, Giuliani headlined a meeting at a Phoenix hotel where he and other Arizona Republicans presented claims of widespread voter fraud.

Now, in a roomful of Republicans gathered for a meeting he requested, the president’s lawyer expected a “friendly crowd.”

It wasn’t.

“I can’t believe how hostile this meeting is,” Giuliani said, according to the recollections of attendees.

Days earlier, Bowers had insisted on evidence from Trump and Giuliani in a private phone call. At the meeting, he said, Giuliani “was getting pummeled on all sides with pointed questions — incisive, pointed questions.”

Bowers left the two-hour meeting underwhelmed by the fraud claims and unwilling to seek to replace Arizona's electors or to hold a hearing on the election.

Eventually, he considered a proposal to an audit of Maricopa County’s election systems, but only with accredited experts and the county’s cooperation.

Fann also left feeling a need to do something, and she seemed willing to move ahead with the joint audit approach.

But during the next two weeks, the Republican leaders’ dual-chamber approach gave way to Fann's Senate-only ballot review. It drew in Trump loyalists from all over the country and shattered the Senate's relations with leaders of the state’s most-populous county.

Fann's decision surprised Bowers.

In a four-month investigation, The Arizona Republic interviewed dozens of people who were in and around the effort to alter the election outcome and the ballot review that for months sustained outrage over Trump’s loss. Some talked on the record about their experiences, while others spoke on the condition they not be identified in order to speak candidly about private conversations.

Democracy in Doubt series Part 1: White House phone calls, baseless charges: The origins of the Arizona election review

The Republic also reviewed thousands of pages of documents obtained through public records requests and through an ongoing lawsuit against the Senate and the company it hired to conduct the ballot review.

Trump and his allies, such as Giuliani and Fann, did not respond to repeated requests for interviews.

Listen to the story: Find the audiobook version of the article below.

Trump loyalists quickly focused on Maricopa County, where Trump lost by 45,109 votes, after winning the county by about the same margin in 2016.

Republican U.S. Reps. Andy Biggs, Paul Gosar and David Schweikert sent a letter to the county Board of Supervisors on Nov. 13, weeks before the results were certified, asking them to manually audit every ballot cast, “allowing tabulators to review ballot images and compare the results to current totals.”

The slim margin between Trump and Biden, “together with questions regarding anomalies and potential errors, is more than enough reasoning” for a full audit, the letter said. An audit would inspire public confidence in the result, it said.

U.S. Rep. Debbie Lesko, R-Ariz., seemed to have doubts. The former PTA mom and state senator, who represents the West Valley, called Clint Hickman, who chaired the county supervisors and also hails from that area.

“What is going on?” she asked. Hickman explained the situation as he saw it.

“It doesn’t feel right. I’m not signing that letter,” the county supervisor remembered Lesko telling him. Lesko did not respond to requests to discuss the matter.

Certifying results: Maricopa County Board of Supervisors votes unanimously to certify election results

In court, the Trump campaign and his GOP allies filed at least eight failed lawsuits in efforts to change the results. The suits ranged from unfounded claims that “Sharpiegate” allowed voters to cast ballots using markers they knew would not be counted to the Arizona Republican Party claiming Maricopa County had too few poll-watchers to handle the signature-verification process.

None of the lawsuits reversed the process.

On Nov. 30, Republican Gov. Doug Ducey sat alongside Secretary of State Katie Hobbs, a Democrat, to sign the official canvass certifying Arizonans voted for Biden. Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, a Republican, watched.

As Ducey signed, the governor received a phone call identifiable by the distinctive ring tone assigned to it: “Hail to the Chief.”

Ducey silenced it.

On the same day, at about the same time, Giuliani and his team appeared about 2 miles away at the Hyatt Regency Phoenix to make claims of widespread election problems: Voting machines could be hacked. Signatures on mail-in ballots were not verified. Arizona, a state of 7 million people, has 5 million illegal immigrants, and surely some of them must have voted.

In fact, tests before and after the election indicated the voting machines counted ballots accurately, suggesting the machines were not hacked.

County election officials did verify the signatures linked to ballots sent by mail. And none of the fewer than 300,000 undocumented immigrants who live in Arizona was known to have voted.

The meeting drew an array of Trump supporters.

Outside The Arizona Republic, a short walk from the hotel, Ali Alexander, organizer of the “Stop the Steal” rallies, used a megaphone as he blasted Ducey for certifying the election results.

A crowd of sign-carrying Trump supporters booed the governor. Jake Angeli, who would become famous as the “QAnon shaman” after the Jan. 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol, howled in disapproval of Ducey and pumped his arms in the air.

Trump supporters protest outside The Republic after Arizona's presidential election results certified

Supporters of President Donald Trump protest outside The Arizona Republic in Phoenix after the election results are certified on Nov. 30, 2020.

Thomas Hawthorne, Arizona Republic

The hotel meeting was a rare opportunity to command national attention for state lawmakers more accustomed to district-level work that confines them to meetings with chambers of commerce, ribbon-cuttings and happy hours with lobbyists.

Until Trump, few had such close contact with the president of the United States and prominent members of his team. Biggs and Gosar sat behind Giuliani’s table. At least nine state lawmakers attended.

State Rep. Mark Finchem, R-Oro Valley, hosted the meeting, which Trump joined by phone. It seemed to bestow newfound importance on a man once ridiculed for wearing a “cowboy costume” at the Legislature.

Finchem, who has described himself as a member of the Oath Keepers right-wing militia group, became one of the leading proponents of an “audit” of the election results. He pressed for a special legislative session to overturn the results and award the state’s electors to Trump.

As much as he wanted to, Finchem did not preside over an official legislative hearing. Bowers refused to authorize it despite Finchem’s repeated requests to hold one at the House of Representatives.

Some lawmakers who attended were clearly starstruck by their sudden proximity to national politics.

Rep. Judy Burges, R-Skull Valley, said of Trump’s team, “They’re so extremely intelligent. You’re just in awe at how much they know.”

Rep. David Cook, R-Globe, said meeting Giuliani was “like meeting a movie star.”

Bowers hadn’t watched the Giuliani meeting the day before, although he heard snippets from a television blaring in his House office. Because Giuliani hadn’t sent the evidence he had promised, Bowers put his attention on other matters.

He recently had prevailed over Finchem to hold onto his title as the House speaker. Winning the battle for the gavel gave Bowers the power to set the chamber’s agenda, decide which bills got heard and help shape the state’s budget.

The 2021 legislative session was nearly upon Bowers, and he needed to prepare. He was at the Capitol, where his artwork — a painting of Cottonwood Wash and a bust of the late Jake Flake, a rancher and Republican state lawmaker — lines the hallway leading to his office, which holds even more art.

During a break from the meeting at the hotel, Giuliani spoke to a House attorney and seemed exasperated. He wanted to be heard by those whose involvement could make a difference.

Bowers agreed to attend a meeting, arranged by the Senate side, a short walk across the Capitol mall complex.

Fann, of Prescott, brought at least one member of her leadership team. Bowers, of Mesa, brought House staff.

Giuliani wanted lawmakers to hold an official legislative hearing so his team could present its case.

“They got the message that the House was not interested — and not friendly,” one attendee recalled.

Giuliani brought Jenna Ellis, the lawyer whom he described as his constitutional law expert; retired Col. Phil Waldron, who cast himself as an election security expert; Katherine Friess, a Washington attorney and onetime lobbyist with past ties to Trump allies Roger Stone and Paul Manafort; and Bernard Kerik, a former New York City police chief who later pleaded guilty to felony crimes for lying and tax evasion.

Conservative activist Lyle Rapacki, who makes videos of his friendly interviews with Trump’s allies, joined the meeting late.

Apart from his political videos, Rapacki manages the Yavapai Patriots, a politically active organization. He also provides conservative commentary to the Prescott eNews, a media website that provides a platform for the local Oath Keepers militia group.

In 1990, Rapacki wrote a book about the widespread problem of satanism. In 2019, an investigation for the Washington state Legislature noted Rapacki was part of a small group getting email updates on an effort led by anti-government militant Ammon Bundy to take over a federal wildlife refuge in Oregon in 2016.

Rapacki’s presence puzzled Bowers and House attendees.

But notably absent were Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich and his staff.

The Trump campaign never formally complained to them about an election Trump still describes as “the crime of the century.”

Giuliani’s team showed lawmakers declarations from concerned voters, election observers and others alleging wide-ranging irregularities on Election Day. They had a handout titled “Arizona ‘Fixing the Vote,’” which purported to show evidence of creating votes for Biden.

Waldron spoke about his work in Antrim County, Michigan, where he was involved in an effort that promoted widely debunked claims that votes were manipulated there. He claimed at the meeting something similar had happened in Arizona.

Ellis, meanwhile, claimed the Legislature had the power to do what it wanted with electors. Bowers asked the presenters if they wanted him to break his oath of office. They said they didn’t.

State Sen. Vince Leach, R-Saddlebrooke, Bowers recalled, “pounded and pounded and pounded” Giuliani’s team over its assertions.

At least twice, attendees recalled, Giuliani remarked, “I can’t believe how hostile this meeting is. I thought we were coming to … a friendly crowd.”

Bowers said there was a reason for the tension.

“We were being asked to do something huge, and we thought we were going to get the evidence at the meeting,” he said.

When the meeting ended, Bowers stood up, walked around the table and thanked the group.

He only shook Waldron’s hand.

“I gotta go,” he said.

House staffers never heard from Trump’s team again.

Giuliani, however, sought to remain in contact with Fann.

Three days after the meeting with him at the Senate, One America News personality Christina Bobb emailed Fann on behalf of Giuliani offering what they viewed as pertinent information and a promise of continued contact.

Unlike traditional journalists who report from the sidelines and maintain neutrality, Bobb helped Giuliani organize witnesses for his Nov. 30 meeting with lawmakers.

“Good morning, Ma’am,” Bobb wrote. “Mayor Giuliani asked me to send you these declarations. He will follow up with you as well.”

Bowers and Fann separately weighed the in-person pitch from Trump’s allies as public pressure from the president’s supporters reached a fevered pitch.

In early December, Trump supporters gathered for rallies to back the president and to implore legislators to decertify the state’s election results. One at the state Capitol, dubbed “Protect the Vote,” attracted some Republican state lawmakers.

Protesters gathered outside the homes of Bowers and Hickman.

Trump supporters called Bowers a pedophile, pervert and traitor in protests that played out through December outside the family house in a county island near Mesa.

Around the same time, dozens of protesters gathered in Hickman’s neighborhood one night carrying candles and screaming, “Honor your oath! Honor your oath!”

Protesters gather outside Clint Hickman's house

An officer's body camera video shows protesters at the home of Clint Hickman, chairman of the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors, on Dec. 21, 2020.

Maricopa County Sheriff's Office

Republicans savaged each other on social media, in part over calls by pro-Trump conservatives for a special legislative session that never happened.

Bowers and Fann kept in near-daily contact and, on Dec. 4, issued a joint statement calling for an independent audit of Maricopa County’s Dominion Voting Systems software and voting machines. That would address the baseless view among some conservatives that the machines were programmed to favor Democrats.

Separately, Bowers released a statement rejecting the calls for a special session by Trump allies.

That statement prompted a phone call from the governor. Ducey told Bowers he had shared his statement with friends. The governor told him he was “proud I was his speaker.”

Four days later, on Dec. 8, Bowers and Fann began meeting over Zoom with Hickman, along with staffers and attorneys for all sides.

They talked cooperatively about various election-related issues. Topics ranged from the sequencing of ballot counting to the status of election-related lawsuits and how an accredited firm could review the Dominion machines. All sides agreed such an audit would give the public a measure of trust in the election systems.

They set another meeting for the next evening, Dec. 9.

That day, Bowers and Fann acknowledged to each other that members of the GOP caucuses still wanted public hearings.

“Karen,” Bowers said, “this is a circus. We’re just making it bigger.”

“I know,” she said, according to his recollection. “But … I think we need to do something.”

Bowers relented and agreed to a joint House-Senate committee hearing. He placed one condition on the joint committee: There would be no subpoenas demanding the county produce information.

Doing so, he feared, would push the county into a defensive posture and pull lawyers into an unwanted battle.

He and Fann agreed it was crucial they acted in unison.

A joint audit was the kind of move favored by Republican Helen Purcell, the former Maricopa County recorder who oversaw elections for decades. At a gathering of Republican women where Bowers spoke, the two hugged and commiserated over the situation. She encouraged Bowers to do an audit.

“You’re going to find out we did it right,” she said.

When it came to examining the machines, Hickman’s main concern was that it happen only after the county was finished defending itself in court. The county’s lawyers didn’t want anyone touching the same voting machines that could be considered evidence in lawsuits.

The county faced the first of at least eight election-related lawsuits on Nov. 7. A federal judge in Phoenix dismissed one of the cases on Dec. 9, momentarily giving county officials a sense that litigation was behind them.

While the county worked collaboratively with Fann and Bowers, Hickman flew in a pair of officials from Pro V&V, an Alabama company accredited by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, to Phoenix. The men planned to examine the Dominion machines.

Hickman said when the technicians were in the air Dec. 9, he learned that Kelli Ward, Arizona Republican Party chairwoman, planned to appeal the judge’s decision, keeping the county in court.

The men stayed overnight at the Courtyard by Marriott in downtown Phoenix, ate at two restaurants and left Arizona the next day.

“They got to watch a rainstorm,” Hickman said. It cost county taxpayers $3,708.

The Zoom meetings were supposed to focus on how a joint hearing between the Senate and House would work. But in a span of days, Fann inexplicably shifted to a new strategy that didn’t involve the House at all.

At one point, attendees remembered Bowers participating from his front porch. They could hear the “Trump Train” yelling vile insults and honking horns as they drove up and down the street.

Meanwhile, Fann sipped wine in her kitchen and cooked chicken chow mein.

The contrast shocked some on the call.

“I was sitting there slack-jawed,” Hickman said. “We couldn’t even talk, it was so loud. We had to kind of wait for a break because it was coming through. Rusty had to put himself on mute.”

A bigger surprise would come as Fann and Bowers remained the target of national pressure from Trump's allies.

On Dec. 10, Fann and state Sen. Eddie Farnsworth, R-Gilbert, the chairman of the Senate’s Judiciary Committee and a longtime friend of Biggs, met with county representatives without Bowers and the House.

The senators told county staff they intended to hold an election-related hearing on Dec. 14, without the House. The hearing would be about tabulation processes, not overturning the results, participants said.

It appeared to be the first time the Senate — it’s not clear whether it was Fann, Farnsworth or someone else — formally discussed at length issuing subpoenas to the county. The requirement to produce documents or other election materials would put the county and the Senate on an adversarial footing because of the legal issues at stake.

That’s why Bowers had opposed subpoenas from the beginning.

County officials were dumbfounded by the proposed maneuver because they already had agreed to appear at the Senate hearing to answer any questions lawmakers had. They had been talking cooperatively with the Senate for days and had the impression they were all moving in the same direction.

“Then, all of a sudden, they started mentioning subpoenas,” said a participant on the call, who took contemporaneous notes. “They started talking about what the subpoenas would look like.”

That prompted Tom Liddy, the head of the Civil Division for the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office, to halt the conversation, given the legal implications.

He remembered something Fann said.

“She said, ‘Well, it wouldn't be a normal subpoena. It would be a friendly subpoena,’” Liddy said. “Of course I laughed.”

She asked Liddy to help draft the subpoena, which was immediately ruled out by lawyers for the county and the Senate.

Liddy is a lifelong Republican, a member of former President George W. Bush's 2000 election legal team and the son of Watergate figure G. Gordon Liddy.

Liddy tried to discourage a subpoena. “You don’t need subpoenas. Just tell us what you want,” Liddy remembered telling Fann.

The timing created additional problems. The Legislature would change in January to reflect those elected in November. Farnsworth was retiring from the Legislature.

Any subpoena from him would expire when his term lapsed. The Senate would need to start over if it still wanted to proceed.

'Fighting for democracy here': Election audit pits Maricopa County Republicans vs. Arizona GOP senators

The county had made clear it had hired Pro V&V to address the concerns over Dominion and hoped the collaborative talks a day earlier, which included the voluntary sharing of information with the Legislature, still would prevail.

And another new phrase was gaining prominence. Fann now wanted what she called a “forensic audit.”

The term “forensic audit” in 2020 election parlance dates to at least Nov. 10, a week after Election Day, when now-former Fox Business Network personality Lou Dobbs called on the air for such an action.

Sidney Powell, a lawyer whom Trump’s campaign had just fired, called for a forensic audit of voting machines in a federal lawsuit filed Nov. 25 against Georgia election officials.

On Dec. 2, Trump called for a forensic audit during a 46-minute video speech from the White House in which he said the nation’s election systems were “under coordinated assault and siege.”

During one phone call with Fann, Hickman asked her to explain what forensic audit meant.

“I need a definition here,” he remembered telling her. “I don’t know what you’re looking for. We keep talking about an audit of the machines and you keep talking of a forensic audit.”

“You know, a forensic audit — of everything,” he recalled her saying. “Everything.”

County Supervisor Steve Gallardo, a Democrat who supported an audit or review with parameters, recalled a similar conversation with Fann. During a quick phone call one evening, he asked her to explain what a forensic audit meant.

She laughed, he said. “I don’t know,” he said she told him. Members of her caucus were “beating down” her door, she told him.

Ahead of the Senate’s Dec. 14 Judiciary Committee hearing, Fann told Bowers her caucus was moving ahead on its own.

“OK. Good luck,” he said. It was the last time he and Fann discussed any ballot review-related matter.

County and legislative officials went into the meeting unsure if there would be subpoenas.

Even one Senate staffer who typically would have been prepared for such a momentous event remembered “not knowing for sure” what would happen.

They only found out at the end of the daylong hearing, which took place by video because of the pandemic. Farnsworth announced he would issue subpoenas. The next day, he did.

One of the subpoenas requested records relating to ranked-choice voting, something Arizona doesn’t have. It suggested to Liddy that Farnsworth, a seasoned lawmaker with a keen grasp of the election process, didn’t write it himself.

Without a single formal vote by members of the Senate, Fann and Farnsworth put the chamber on a path to review the Maricopa County ballots.

Under pressure from Trump and his supporters, Fann appeared to be looking for a way to defuse the anger. Months later, many still can't understand her go-it-alone approach.

The surprise subpoenas, which the county immediately challenged, dashed hopes for a cooperative effort to understand the election’s results.

Days later, Bowers expressed his disappointment about the situation to Hickman.

“I wanted you to know I said we would be willing to join the senate in a joint committee but I would not authorize my chairman to subpoena the county,” the speaker wrote in a text to the supervisor.

“The senate went on alone and I am not happy with that outcome.”

Hickman appreciated the outreach in his return text.

“Almost 7 hours of testimony, answering all questions they had...still resulted in a predestined conclusion. I sent Karen a two word text: NOT HAPPY. Thank you for sticking with us. It’s called rational leadership in irrational times and I am positive history will be kind to us.”

Bowers said he still has no idea what led Fann to shift from a cooperative, joint audit to pursue the ballot review that has played out.

“It’s one of the nagging mysteries,” he said.

Trump supporters quickly returned to protesting outside the homes of Bowers, Hickman and others.

The pushback swelled into an effort later that month to try to recall Hickman and other Republicans on the county board. Bowers later faced a similar recall effort.

Hickman worried about his safety and had a protective security detail for the remainder of his tenure as board chairman, which ended Jan. 6.

The subpoenas pushed the county into a battle with the Senate over what the county could produce without creating evidentiary problems in its lawsuit, and without running afoul of state laws over handling ballots.

The fight between the county and the Senate over the subpoenas would spill past Jan. 6, when Congress was required to certify the national election results.

There were more surprises in the final days of the year, with two members of Arizona's congressional delegation continuing to assert widespread fraud in Maricopa County’s numbers.

On Dec. 21, Gosar, Biggs, Finchem and Gosar’s chief of staff held a two-hour video conference with Bowers.

It featured a presentation from the newly formed Data Integrity Group, whose members described themselves as concerned “numbers guys” who saw things that “didn’t add up.” They gave a similar talk to members of the Georgia state Senate nine days later.

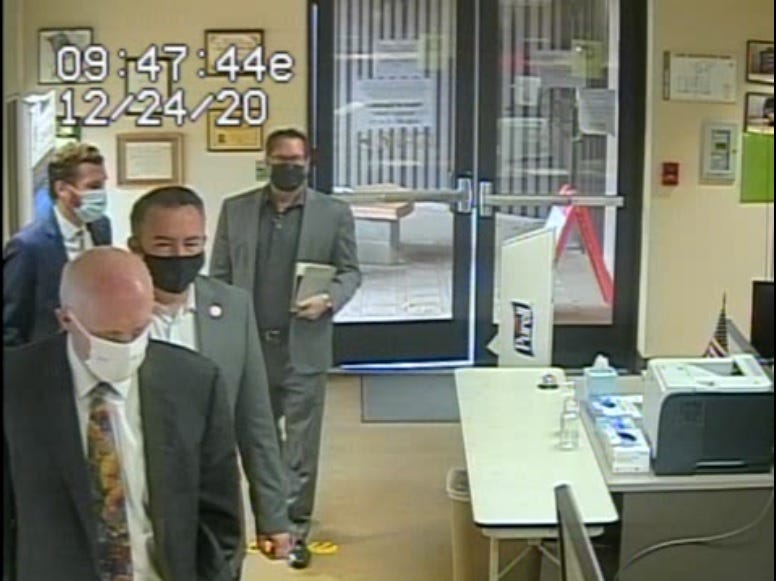

Arizona House Speaker Rusty Bowers meets with Data Integrity Group

Arizona House Speaker Rusty Bowers hears a presentation from the Data Integrity Group on Dec. 21, 2020. Also on the Zoom call were Republican U.S. Reps. Paul Gosar and Andy Biggs of Arizona and state Rep. Mark Finchem, R-Oro Valley.

Arizona Legislature

Their presentation was intended to dazzle Bowers, but it started with a disturbing metaphor about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and never provided the kind of concrete evidence the speaker wanted.

“We’re here to basically calm down all these questions, all these people that are saying, ‘Hey, JFK is perfectly alive, and we should just move on with everything.’ We’re here to show you the corpse and the bullet in the back of the head,” said Justin Mealey, a Navy veteran whose professional biography said he had contracted with the Central Intelligence Agency.

“We can prove that early voting could not have occurred as reported without massive fraudulent voting.”

Their analysis was based on a feed of vote tallies, not information directly from the county. They claimed Trump’s vote totals sometimes moved down. Maricopa County officials said their actual data shows all vote totals grew as ballots were counted.

Bowers likened the election result to Politics 101: Voters liked Biden more than Trump. He reminded the presenters of the first presidential debate between the rivals, where Trump and Biden traded insults and talked over each other.

“I saw that debate,” Bowers told the presenters. “I said, ‘The president just lost this race.’”

Finchem wanted Bowers to ask recorders in three other Arizona counties to participate in forensic audits as well.

Bowers agreed to take the group’s concerns to Maricopa County election officials, but without evidence of widespread fraud he refused to throw out the votes of 3.4 million Arizona voters.

When Mealey questioned whether even that figure was reliable, Bowers grew testy.

“Maybe there’s a bot in Bulgaria,” he said. “I don’t want to tie into hysteria.

“I’m not going to throw out the vote and say we’ve got to recount this because there’s one fraudulent vote,” Bowers said.

The holidays were drawing near, with the congressional certification of the election results scheduled not long after.

The day after the video conference, Bowers pressed on with his fact-finding.

He had been working the phones, asking election officials in other counties how they felt about their election processes at that point. They all felt pretty good.

Bowers took a breather on his front porch after talking to the manager of Coconino County. A Washington, D.C., number popped up on his phone.

“I’m calling for the president. Can you take this call?” a friendly sounding woman on the other end said.

He and Trump talked for 10 minutes. Trump seemed to remember Bowers’ position from their last conversation about trying to get him to decertify the election. But it also seemed Trump hadn’t been told that Bowers had deemed Giuilani’s efforts “breathtaking” and illegal.

“I’m all about every legal way to help,” he told the president.

The men wished each other a Merry Christmas.

Trump didn’t ask Bowers for anything.

The speaker thought the call was a “nice” gesture from a man he could like aside from his tweets and other personal characteristics.

“I feel many times like I’m Charlie Chaplin teetering down the alley with my little hat, digging out fish bones … and then leaning against the door and falling into the king's ball,” he said of an experience that seemed surreal.

Two days later, on Christmas Eve morning, Maricopa County election officials met with Bowers, his majority leader, Rep. Ben Toma, R-Peoria, and their staff.

They got a full rundown of how elections in the state’s biggest county work, from start to finish.

For hours, election officials showed them how they prepare for elections, how tabulation machines work, protocols for touching ballots, and the vault that holds the ballots.

They saw the Dominion machines were not hooked up to the internet, contrary to one conspiracy. In a conference room, the lawmakers and staff were handed test ballots and markers for a demonstration disproving the Sharpiegate theory.

Even on this tour, the county enforced its prohibition against allowing unauthorized people to enter the area where ballots were stored.

Election officials disproved the Data Integrity team’s presentation, in some cases slide-by-slide. The county rebutted claims of vote injections for any party.

That same day, Giuliani reached out to two of Hickman’s Republican colleagues on the board: Bill Gates and Jack Sellers.

“I’m hoping we could have a chance to have a conversation,” a transcription of Giuliani’s message to Sellers said. “I’d like to see if there’s a way that we can resolve this so that it comes out well for everyone. We’re all Republicans, I think we have the same goal. … Let’s see if we can get this done outside of the court, gosh.”

Sellers did not return the call.

Trump and his allies weren’t done yet.

Trump allies leave voicemail messages for Maricopa County supervisors

Maricopa County supervisors got texts and phone calls from the Arizona Republican Party chair, the president’s personal attorney and the White House as votes were counted in the November election and as those results were contested. Here are some of the calls.

Arizona Republic

On New Year’s Eve, while Hickman was on a dinner date with his wife and friends, his phone rang. He didn’t recognize the phone number coming from Washington, D.C., and let it go to voicemail, then listened to the message.

The White House switchboard wanted him to call back so he could talk to the president. He didn’t call back.

On Jan. 3, Trump called Hickman, who again didn’t answer. Hickman saw the Washington Post had just reported that Trump had pressured Georgia’s secretary of state to “find” enough votes to make Trump the winner in that state.

The next day, John Eastman, dean of Chapman University's law school in Orange, California, laid out a legal theory to Bowers and his staff.

Eastman has radical views on the law. He controversially argued in Newsweek that Vice President Kamala Harris was ineligible for her office because her parents were immigrants, a fringe view that helped lead him to retire from Chapman under pressure.

On this day, Eastman explained how and why Arizona’s electors should be rejected before the upcoming meeting of Congress to formally certify the electoral results.

John Eastman spreads claims of election fraud at Jan. 6 rally

Chapman University law school Dean John Eastman discusses unfounded claims of election interference as Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani looks on at a rally on Jan. 6, 2021, in Washington, D.C.

C-SPAN

Almost all the examples Eastman cited in his reasoning for dismissing the results of Arizona’s election stemmed from Georgia, Pennsylvania and elsewhere, those in attendance recalled.

“You’re the president’s lawyer, and I appreciate you’re doing this job,” Bowers said. “Has this ever been done before?”

No, Eastman said. But he encouraged them to give the strategy a shot and let Trump’s legal team worry about the litigation.

“It’s never been done in the history of the country,” Bowers said, “and I’m going to do that in Arizona? No.”

Behind the scenes, Biggs made one final push to change the election.

He called Bowers, a longtime East Valley Republican associate, on the morning of Jan. 6 and asked if he would support decertifying Arizona’s electors. Bowers said he would not.

On that day — when Congress was to certify presidential election results — Trump and his allies spoke to thousands of his supporters from the Ellipse, a park south of the White House.

“States want to revote,” Trump said. “The states got defrauded. They were given false information. They voted on it, now they want to recertify. They want it back.”

Biggs later stood on the floor of the House of Representatives and urged his colleagues to set aside electors from Arizona, Georgia and other states, arguing the election rules in those states had shifted during the voting period and thwarted the Legislature’s control over how to select its electors.

U.S. Rep. Andy Biggs challenges Arizona electors on House floor on Jan. 6, 2021

U.S. Rep. Andy Biggs, R-Ariz., objects to counting the votes of Arizona's electors on the House floor on Jan 6, 2021.

C-SPAN

“The Arizona Legislature seeks an independent audit of the election,” Biggs told the House, perhaps leaving the impression that both of the state’s legislative chambers were moving to do so.

Before the House voted to reject Biggs’ arguments, hundreds of Trump supporters broke into the U.S. Capitol, sparking a deadly riot.

Includes information from Arizona Republic reporter Mary Jo Pitzl.

Coming Friday: Trump’s grip on Arizona GOP

"results" - Google News

November 18, 2021 at 11:14PM

https://ift.tt/3kQK7fz

'Asked to do something huge': An audacious pitch to reverse Arizona's election results - AZCentral.com

"results" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2SvRPxx

https://ift.tt/2Wp5bNh

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "'Asked to do something huge': An audacious pitch to reverse Arizona's election results - AZCentral.com"

Post a Comment