It is legally required for the winner of a U.S. presidential election to be declared on the same day as the election.

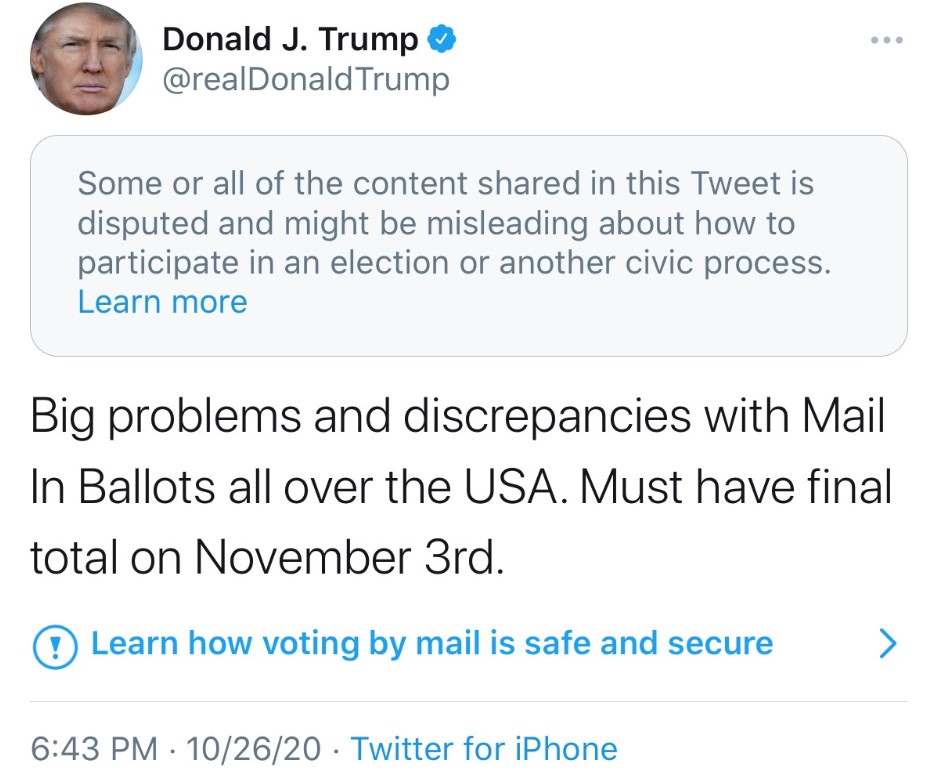

On Oct. 26, 2020, U.S. President Donald Trump posted a message on Twitter stating that we “must have final [vote] total” of the presidential election on Nov. 3, 2020. This tweet was subsequently flagged by Twitter for spreading content that could damage the integrity of the country’s elections:

This is not the first time that Trump has called for the winner of the election to be declared on Nov. 3. On Oct. 27, Trump said:“It would be very very proper and very nice if a winner were declared on November 3rd, instead of counting ballots for two weeks, which is totally inappropriate and I don’t believe that that’s by our laws. I don’t believe that. So we’ll see what happens.”

The laws of the United States do not say that the winner of a presidential election must be declared or certified on the same night as the election. In fact, the election process in the United States extends for several weeks after the final votes are cast on Nov. 3.

While Americans may be used to seeing newscasters call the results of a presidential election on election night, states don’t typically certify their election results for several days (and in some cases weeks) after the election. When a newscaster “calls” a race on election night, this is actually a “projection” — an estimate based on the amount of votes cast so far — and not a legally sanctioned election result.

Here’s an excerpt from an article published by Pew Research concerning American’s skewed expectations for election night:

On Nov. 3, millions of Americans will trek to their local polling places to cast their ballots for the next president. That evening, after the polls close, they’ll settle down in front of their televisions to watch the returns roll in from across the country. Sometime that night or early the next morning, the networks and wire services will call the race, and Americans will know whether President Donald Trump has won a second term or been ousted by former Vice President Joe Biden.

Just about every statement in the previous paragraph is false, misleading or at best lacking important context.

Over the years, Americans have gotten used to their election nights coming off like a well-produced game show, with the big reveal coming before bedtime (a few exceptions like the 2000 election notwithstanding). In truth, they’ve never been quite as simple or straightforward as they appeared. And this year, which has already upended so much of what Americans took for granted, seems poised to expose some of the wheezy 18th- and 19th-century mechanisms that still shape the way a president is elected in the 21st century.

While Nov. 3 marks the end of voting, it is far from the end of the election process. In the following days and weeks (it varies by states), all of the ballots will be counted and certified. This year, the process might take an especially long time due to an expected increase in voter turnout, as well as a surge in mail-in ballots due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Many states continue to receive and count mail-in ballots for several days after election day as long as those ballots were postmarked on or prior to Nov. 3. In Mississippi, for instance, absentee ballots will be accepted “five business days after Election Day if postmarked on or before Election Day.” In Illinois, ballots that were postmarked on or before election day will be counted as long as they arrive within 14 days. In other words, we won’t know the official total vote count on Nov. 3 because some states won’t even be finished receiving ballots by this date.

And counting ballots is only part of the process.

The President of the United States is not elected by the popular vote. Rather, once each state counts and certifies all of its votes, governors prepare a “Certificate of Ascertainment” that lists the state’s Electoral College electors. These electors cast their votes for president, which are then counted and certified by Congress.

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), an independent government agency tasked with preserving historical records, is responsible for transmitting the votes of the Electoral College to Congress. In NARA’s guide to the 2020 election, they outline a timeline that stretches from June (when preparations begin) to Nov. 3 (when the election takes place) to mid-November (when governors prepare a “Certificate of Ascertainment” listing the state’s electors) to Dec. 14 (when members of the Electoral College cast their votes) to Jan. 6 (when the vote is counted in Congress) to Jan. 20 (when a president is inaugurated).

Review NARA’s full timeline in this document.

In short, tallying the vote this year is expected to take longer than usual due to increased voter turnout and a surge in mail-in ballots. While it is possible that one candidate will win enough votes on election night that newscasters will be able to say with reasonable certainty who will win the election, these news reports are not the official legal method in which a presidential election is certified. States will spend days (or weeks) counting ballots in the days after the election, governors will then certify those results and list their electors, members of the electoral college will then cast their votes, and then Congress will certify those results.

"results" - Google News

October 28, 2020 at 03:17AM

https://ift.tt/3mnMRiI

Are US Election Results Required To Be Certified on Election Night? - Snopes.com

"results" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2SvRPxx

https://ift.tt/2Wp5bNh

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Are US Election Results Required To Be Certified on Election Night? - Snopes.com"

Post a Comment